Nearly six decades after Russia’s tiny Sputnik 1 made satellite history, the Bay Area has become a launchpad for a new type of space race.

As many as a dozen local ventures, with names like Planet, SpaceVR and Terra Bella, are building their own constellations of nanosatellites to send into orbit around the Earth.

Also known as CubeSats, these satellites can be as small as a loaf of bread but powerful enough to beam back images or data that can be used by farmers, rescue workers, weather forecasters and even hedge fund managers.

“What I love about this sector is that five years ago, almost no one was actively investing in it — it was just a dead zone,” said venture capitalist Steve Jurvetson, a partner with Draper Fisher Jurvetson and an investor in Planet and SpaceX. Now, as the sector takes flight, he believes small satellites will eventually have an economic impact comparable to the transition from “mainframe to mobile computers.”

The same mobile phone technologies, such as processing chips and sensors, that have upended the consumer world have also made it cheaper and quicker to build CubeSats. So it’s less financially catastrophic if the rockets that launch them into space fail. (The Facebook-backed satellite that blew up this month at a prelaunch SpaceX rocket test in Cape Canaveral was the size of a truck and weighed about six tons.)

Photo: Michael Macor, The Chronicle

An infrared image taken by a Planet satellite shows Oakland International Airport and the island of Alameda.

“Over the next two years, we’re going to see an explosion of data coming from these companies,” said Sean Casey, founder of the Silicon Valley Space Center.

While traditional satellites can cost up to $1 billion, CubeSats use more off-the-shelf components and can be built for less than $100,000, according to Dick Rocket, CEO of NewSpace Global, a Cape Canaveral space industry analytics firm.

“I don’t really think of us as a space company,” said Will Marshall, CEO of San Francisco’s Planet, which he co-founded in 2010. “I think of us as a data and software company. We happen to have some assets in space that enable that.”

Marshall likes to say that his company has made San Francisco the world leader in satellite manufacturing. Planet already has 60 digital imaging satellites in orbit, including eight deployed earlier this month from the International Space Station. Employees in its South of Market headquarters are busy assembling 100 more satellites that the company wants to launch within the next year. The two-story building, a 1940s-era warehouse, also has a testing chamber that simulates the cold, harsh conditions of space, and a “mission control” section next to an employee work break area.

Planet has “launched more than most nation states,” said Micah Walter-Range, director of research analysis for the Space Foundation, a Colorado commercial space educational group.

The larger traditional communications satellites, which orbit farther from the Earth than Planet’s small satellites, still make up the bulk of the industry’s revenue. But in the past three years, satellite launches have increased from about 100 to 150 per year to 200 to 300 a year, and “that’s almost entirely due to nanosatellites,” Walter-Range said.

In a report released this month, NewSpace Global said 72 small satellites have been launched this year, with another 174 planned before year’s end. Investors have poured $4.52 billion into the small-satellite market since 2011.

Planet’s satellites, named Doves, don’t have their own propulsion system and can’t sustain their orbit over the long haul. Planet expects each to fall back into the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up after two or three years in orbit. The company plans for about a 20 percent failure rate.

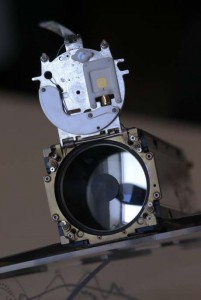

Photo: Michael Macor, The Chronicle.

A telescope is inside a satellite that gathers images of Earth sits in the San Francisco headquarters of Planet, which creates shoe-box size satellites.

“We think of them like disposable assets,” Marshall said. “If one doesn’t work, OK.”

The Doves are 4‑by-12-inch rectangular boxes with solar panel wings. (By comparison, the ball-shaped Sputnik 1 was 22 inches in diameter.) They are packed with high-resolution cameras that can pick out vehicles, vessels and trees from as high as 295 miles above Earth.

CubeSats are small enough that “you could put them all in a single launch vehicle to get them up there because they’re so tiny,” Walter-Range said.

But rocket launch failures have taken their toll. Planet lost 28 satellites in an October 2014 explosion of an Antares rocket lifting off from Virginia, and lost eight more in a June 2015 explosion of a SpaceX rocket from Cape Canaveral.

Dick Rocket of NewSpace Global said small-satellite companies can’t turn a profit until the commercial space industry can improve the rockets’ reliability.

“Once we begin to have launches at rates that are significantly higher than has ever been done, then we’ll see these small-satellite ventures do the things that are truly transformative, like predicting the weather, providing high-definition images from space, expanding our understanding of nature,” he said.

Marshall said Planet can make a profit if it can meet its goal of having 150 nanosatellites constantly in orbit, providing a daily snapshot of “every single inch of the Earth.” Instead of images every few weeks or months provided by traditional satellites, frequent images make even subtle changes on the ground more visible, and the results are telling, he said.

For example, Planet’s images were used by the Amazon Conservation Association to uncover an illegal gold mining operation in Peru earlier this year, while rescuers in Nepal were alerted to remote villages covered in mudslides after the April 2015 earthquake. The satellites have also captured detailed images of the devastation caused by recent California forest fires, and the spread of Syrian refugee camps.

“We can pick up any issues not visible with the naked eye, big or small,” said Marina Barnes, vice president of marketing for Farmers Edge, a Canadian company that sells crop-management technology to farmers. Since the resolution can detect changes in about a 16-foot section of land, the satellites can help farmers see if a particular section of crops are over-watered or under-fertilized, she said.

Farmers Edge buys Planet’s images because they provide more frequent updates than older satellites, which might miss weeks worth of changes if the farmer’s fields are covered with clouds during a fly-over, Barnes said.

Some big names have embraced the small satellites. Google subsidiary Terra Bella, once named Skybox Imaging, had four small satellites launched into orbit this month, according to the industry publication SpaceNews.

Aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, which built its first communications satellite in 1958, is experimenting with CubeSats for Earth science missions and for government customers, said Stephen Frick, a former NASA astronaut who is now director of Lockheed’s Space Systems Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto. Lockheed is also researching how NASA’s deep-space Orion missions could take CubeSats “to the moon or farther,” he said.

Other companies are building just one satellite — like San Francisco’s SpaceVR, which aims to put a virtual reality satellite into orbit in 2017.

Spire Global, another San Francisco company, has two types of satellites, one used for ship tracking and the other for precise weather measurements of the atmosphere; so far the company has launched 17.

Spokesman Nick Allain said his company, which makes its satellites in the United Kingdom, considers itself a data-collection firm, not a space company. CubeSats, he said, will “never fully replace traditional satellites.”

“Some instruments are simply too large to fit into a CubeSat,” Allain said. “Where satellites the size of Spire’s excel is in passively capturing radio signals using deployable antennas, in capturing data in very high speed about the entire planet at once and in having high system reliability.”

“One failure,” he added, “doesn’t take down the system.”

Source: SF Chronicle

Benny Evangelista is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: bevangelista@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ChronicleBenny